Parental guidance

Heather Pearson examines emotional growth, how to get it when parents are in short supply and how, whether we want it or not, emotional growth sometimes creeps into life anyway, making us brave, honing instincts and identity.

Words by Heather Pearson.

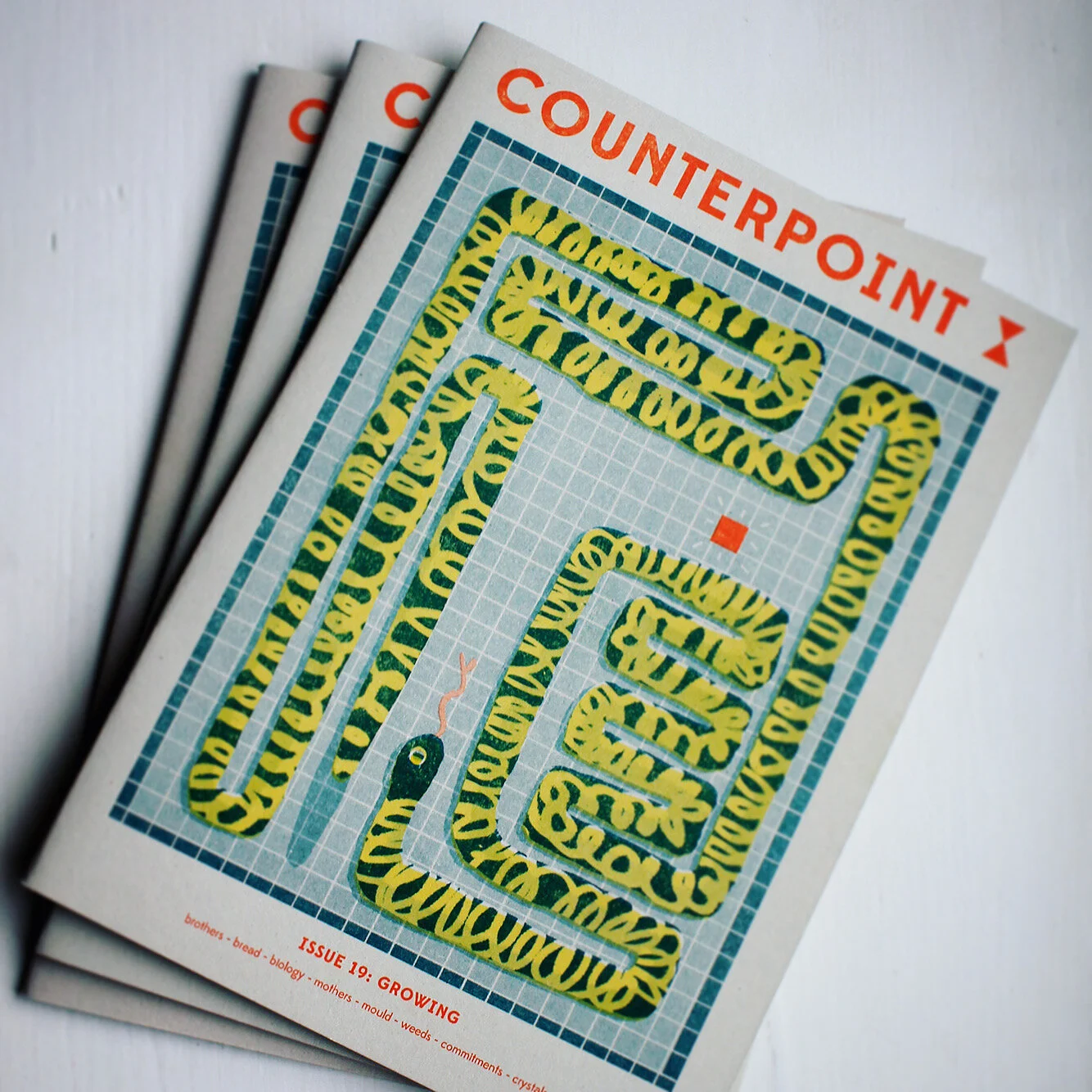

Illustration by Miranda Stuart (detail above).

I have a friend who prides herself on staying the same. ‘I haven’t changed, have I?’, she asks me every few years, keen to be affirmed in her endurance of self-image sameness. She sees herself as an anchor for others, too, knowing the huge comfort of consistency, staying very close to where she was born and raised with a fervent, often enviable loyalty and impassioned commitment. I, on the other hand, having had a less geographically consistent upbringing, am more of a sand dune; my mass splitting and shape-shifting with the weather, back and forth across three Scottish cities and a string of Hebridean islands, the tidal grains of me.

And yet, we each grow, her and I. We’ve each lost a beloved parent, and we’ve each found wisdom from other sources in parental absence to allow emotional growth from grief, too. She leans in closer to her remaining parent and step-parent and also to playing live traditional music in informal Sunday village pub sessions. The playing stretches and challenges her with the comfort of other musicians doing the same thing alongside, sharing what they’ve learned along the way, not just about their instruments or the stories behind the pieces they play, but also about themselves and how they’ve often had to shelf ego to allow learning a tricky piece so mistakes, public, audible and inevitable, then transform into growth.

Being largely estranged from my dad for many years, I find myself secretly co-opting missing father and mother-love and wisdom from other older women. An aunt and my mum’s best friend check-in on me as tribute to their missing sister. Writing workshops have been a gift not just in improving my literacy but also in giving opportunities to meet a few feminist women ten to thirty years further down the road, each of them shining with a visceral clarity of view about the way things are, have been and will be. These women draw me, in their wisdom lies shortcuts to emotional growth if, I have learned, I just listen and reflect.

An Afghan friend my own age explained last year she also seeks out friendships with older women with a tacit purpose of finding companionship that includes emotional mentoring. We laughed at our not so covert missions to lovingly ingratiate ourselves with elders, my motivation borne of grief, hers from being markedly more westernised than her parents after twenty years in the UK and feeling increasingly at sea without approving corrections, nods and charting through her evolved identity. Older women, we realised, were keeping us both sane, keeping us both growing so we could protect ourselves and stay open, too.

The first time I was knowingly given the opportunity for emotional growth I refused it. “If you only read one more book in your life, make it this one”, my mum had near begged, pressing Gloria Steinem’s Revolution from Within into my fourteen-year-old hands as my lip curdled, cringing at the cover photo of a deeply middle-parted woman. Mum went on, “you need self-esteem, girls with fathers in pain especially do. If you read this it’s a headstart you’ll never regret, I promise.” I backed away, up three more of the stairs behind me while she stayed planted on the living room carpet.

My coping with a father in pain consisted then of blotting it out, getting high or drunk often so I could put truth to the words, ‘I don’t care’, when intrusive thoughts about paternal rejection showed up. I needed distance from the mention of my dad. A throbbing hurt had tucked under my sternum since he’d explained their marriage was over and he needed freedom and the beat of the throbbing rushed faster when mum even remotely referenced it. I’d renamed the hurt Anger the year before it was a year old, privately nurturing it like a parasite in my ribcage. Any sign of tears during ‘quality time’ with my dad and, bless him, he’d be noting exits, becoming a glinting sliver of parent; one moment a knife edge, the next a shard of ice, impossible all ways to match with verses in Father’s Day cards.

‘Feelings’, mum’s post-divorce buzzword, made me frightened that what was intermittently offered of my dad would shrink further still. Mum, oblivious, ushered in feelings at every juncture, embarking on emotional growth as a single woman as her seminal work. Feelings after teeth brushing. Feelings while we did the dishes. Feelings while the kettle boiled. Feelings on toast. Feelings at Asda while searching for the smart-price beans. Feelings in letters to school teachers to appraise them of my feelings and inviting them to share their feelings, in response.

Safer then, I reckoned that day on the stairs, to reject the concept of emotional growth completely. I didn’t mean for the book to jab her in the tit when I’d chucked it, her hands rushing to where a bruise would soon bloom. Our eyes had locked while Gloria’s face tumbled, happy and frozen, then disappeared, her centermost pages fanning, flopping and parting from one side to the other, undecided whether to land with the front or back cover. Mum blinked hard and fast, tears welling then spilling. My hands shot to my mouth, the pernicious shit of the parasite inside puppeteering, commanding me not to apologise, sure somehow it was Mum’s fault anyway, all of it, because she’d tried to make me less like me. In those moments, we were the slow-mo end of my parent’s marriage in miniature, high-speed vignette. One wanting to grow and glow, the other wanting less talking, less responsibility, less of everything. I turned and ran up the stairs, slamming my door behind me.

We went on like that, more or less, for another six months; me, volatile and metaphysically mute and her, quietly resolved and replenishing herself from freshly burgeoning shelves of self-help volumes at the library.

Then, one night in a bathroom at a house party of a friend whose parents had gone away for the night, I was offered heroin. This fine brown dust had been making its way nearer our group of tearaways for the entire year previous, closing in on us inch by inch, party by party, person by person, the bubbling creep on a teaspoon forming a quiet tide at the edges of our wild existences. I eyed the pivot point from my perch on the edge of an avocado bath. I looked up at a whole family’s toothbrushes in a green ceramic holder on the windowsill: mother, father, son, daughter. Unusual, in my circles. I flicked fag ash into the sink and the bristle-faced toothbrush family whispered about my mum. What would she do, if I took smack and died? It was a possibility I knew about, even for a first-timer. Was there a self-help book for the death of an angry child? Even if there was, I knew instinctively the book mum would need to be without me, or my sister, would never help her. I got up from the side of the bath, said no thanks, dropped my fag end out the open window and went home.

Mum woke with a start in her armchair when I opened the front door. ‘What time is it?’, she asked, patting her chest, trying to find her specs.

“Half one”, I’d replied. “Early, for you…” “I’m sorry, Mum. For the book. And your tit.” When I eventually worked through the burn of my awkwardness enough to look up, I found her smiling. I felt peace, the first in a long time. I flopped down on the sofa across from her, grateful too that I was loved enough, and scared enough of what I already knew about loss, to know when to say no. We talked it all through. Then, after a long yawn, she reached to the bookshelf at her side and pulled out Gloria. Leaning forward, she extended her arm, “ready?”

I nodded, stretched up and caught the book in mid-air. Ready. Across many years since my mum’s death and The Sea of Feelings, my estranged dad and I have struck up a conversation over text that’s approaching its first birthday. We talk a little about birds in our gardens, about our separate Christmases, birthdays, work and families. Neutral topics. Safe islands. It’s tentative and fragile, a porcelain filament sculpture I cannot yet dance or stomp anywhere near, lest it smashes. I dream of a day when I can provide comfort when he’s unsure of life or death, and vice versa, when we can safely laugh together and, dare I dream, cry, too. The hope, borne of emotional growth, is an act of faith and self-love from seeds planted by mum and Gloria, long ago.